Whether you’re a student or a pharmacist, this guide is just meant to be a “quick” rundown for people who want to get into industry but don’t know how. If you have any feedback on the guide, have questions about industry, want tips on how to secure your first job, or anything else, hit up u/AdenosineDiphosphate on Reddit. You can pay for one of those career consulting services for hundreds of dollars online, or you can ask me for free. No guarantees I’ll get you to land a job though.

If you’re a professional in industry, I’d love any and all feedback you have. I’m here to make a better guide so shoot me a DM and I’ll try to incorporate what you have.

As for the guide itself, sorry if it’s ugly or poorly formatted. It was originally a Google Doc, but I wanted to keep track of how many views it got, so here we are. For the Google Doc link, click here:

Topics Covered (just ctrl+f to get there):

Benefits of Industry

Breakdown of Industry

Getting into Industry

The Resume

Also, if you’re a student or recently graduated pharmacist looking to get a fellowship, check out the new fellowship guide:

Benefits of Industry

Before we even start the guide, you might be wondering why you would want to pursue a career in industry. This guide is not meant to convince you to join the dark side. This guide is simply here to help people understand what industry is, what to expect out of it, and how they can get there should they so choose. Also, be aware that industry may not be a dream job for you and it will not necessarily resolve your work discontent. It doesn’t have the same negatives of retail, but every job has its downsides, like bringing your work home and no extra pay for OT.

Besides the obvious benefit of not being retail, there are a lot of benefits that come with working in industry. In retail, there’s a pretty hard cap on how high you can go. In industry, the sky’s the limit with directors making north of $200k/yr alongside PTO, stock options, WFH capabilities, bonuses, and more. There is also the opportunity for horizontal movement. In retail, if you hate what you’re doing, you’re going to need a new SSRI for yourself. In industry, if you hate what you’re doing, you have the option to go to another department. Decide you’re over submissions and want to get more in the research side of things? Switch from reg to clin dev. Talking with doctors is too much for you and you want more impact on the patients themselves? Switch from MSL to patient advocacy. Industry is great for both vertical and horizontal flexibility. You also don’t need your license for a majority of positions which is a plus if you hate CEs or just don’t want to take the NAPLEX.

u/ValueDohaeris created a survey on Reddit that showcases expected salaries and benefits for those in industry: https://www.reddit.com/r/pharmaindustry/comments/mrs5zw/pharmaindustry_compensation_survey/

Results here: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/10prU-_o_NGsgrIuoUXmvBQgX13NAdS-0fWQiatn9DsY/edit?usp=sharing

Breakdown of Industry

Each functional area in industry has its own generic traits which attract different kinds of people. While these functional areas vary in role and purpose from company to company, there are many obvious commonalities between them. Below are highlights of the main details from each one as well as a few sub-branches. These are not all the roles nor do the descriptions encompass everything the role does; there are so many details that this guide would become an encyclopedia if we included everything. These are just the main things that you’ll see and hear about as a PharmD. If any people in these fields want to correct what I’ve written or add onto it, message me and I can edit these descriptions.

Medical Affairs: This is where most PharmDs going through a fellowship go. They are one of the most clinically-inclined groups. Their main function is to share scientific knowledge and clinical advancements with the rest of the medical community while also receiving input from the community to help guide which direction the company should go.

Medical Science Liaison (MSL): MSLs are the ones who go to doctors’ offices and conduct field rides to share knowledge with Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs). That’s their main job: to share knowledge. They want to know what the doctors know about the disease state as well as share with the doctors what the newest developments are for that disease state. This way, pharma can have an open communication path with medical professionals. Their role benefits the entire health care field because they fill the gaps that we don't know while also trying to meet the goals of the doctors. Doctors want to know who the major patient population is for a disease state or where the major treatment centers are? MSLs can answer that. Doctors want more research on X antibody because they believe it has a huge influence on the pathogenesis of a disease? MSLs relay that to the industry so they can conduct trials and find the answer. Important note: MSLs are NOT commercial. They are not allowed to recommend a doctor use their medication or solicit the use of their product. It is against company policy, illegal, and a huge misconception people have.

Medical Information (Med Info): You ever have a question and want to call the company that made the drug to get a straight and scientifically correct answer? You’d call the company and get directed to a call center where people answer your questions. That is med info's job. They look through trials, existing data, literature, publications, etc. to find answers to inquiries related to a specific drug product. The questions get placed into tiers. Tier 1 questions are the most straightforward questions that don’t require a ton of digging to find while the higher tier questions generally require more in-depth searches. For you PharmDs who want to get into industry from a non-industry setting, this is one of the entry-level positions you should apply for.

Medical Communications & Publications: Whenever a trial finishes, the results have to get published somewhere, whether it’s at a conference (also known as congress for whatever reason) or in a medical journal. These guys are in charge of drafting and submitting these publications, making sure the information is scientifically sound. They make abstracts, posters, manuscripts, advisory boards, and publications among other things.

Health Economics and Outcomes Research (HEOR): They're the ones who conduct HEOR (duh) to see how well the drug is being utilized/going to be utilized to estimate how much the drug needs to cost to outweigh all the other costs, like R&D and commercialization. They work closely with other departments in commercial, such as market access, to make sure the drug price is affordable and attainable. They can then present this information to insurance companies so that they will add it to their formulary. Because not everything that happens in a clinical trial setting is reflective of what happens outside of the lab, HEOR teams also have to factor how the drug is going to actually be used. They compile details using claims data, electronic medical record information, Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs), Real-World Evidence (RWE) studies, and other figures to determine the value of the drug. They can then use this information to work with the hospitals and healthcare systems to generate value-based contracts where the hospitals only pay for the drug based on the expected value of the drug. If the drug doesn’t meet the specified metrics, then the hospital doesn’t have to pay the full price. A lot of managed care pharmacists, P&T pharmacists, and AMCP students who decide they don’t want to go the managed care route find themselves drawn to HEOR because of the overlap in skills and goals. If you’re good with numbers and can make things like budget impact models and handle ICER stuff, this could be a good field for you.

Other: Larger companies will further differentiate roles into functions such as medical strategy, medical education (the people who create internally facing training documents for the MSL teams and sales teams), and more.

Regulatory Affairs: In the pharmaceutical industry, every company has to get their drugs approved by a regulatory body somehow, whether it be the FDA in America, EMA in Europe, PMDA in Japan, or somebody else. This department is in charge of getting the files and trial data together to submit a drug application along with a few other things. They serve as the liaison both internally, working with all the different functional areas to get submissions and communications out, and externally, responding to any inquiries from FDA and the global health authorities.

Regulatory Strategy: How do we get the drug approved? What did other companies do? How did the approval pathway they use help and hurt them? What can we do to expedite the process so people can start using the drug earlier? Most importantly, what trials are we going to really sell to the regulatory body to say our drug is both safe and efficacious? How do we explain that the one trial that failed was a fluke and that the rest that succeeded are the ones they need to focus on? What approval pathway do we use and how does it apply to our drug? These are all questions that reg strat think about and answer on a daily basis. They are the overarching brains of the operation on the regulatory team and dictate where the strategy goes (duh).

Medical Writing: The people who are in charge of filling out the submission documents. It's usually the entry-level position that many PharmDs try to get into. When anything has to be submitted, the medical writing team is in charge of pulling in all the relevant information (clinical trial information, specific site information, Investigator’s Brochure details, etc.) and sending it over to the submissions team to compile. To excel in this role, you should have pretty good experience or knowledge in technical writing. Note: medical writing can also be considered a medical affairs job under med comms depending on what the majority of their writing projects are (submissions vs. literature).

Submissions: As the name implies, this team is in charge of compiling the submission documents and getting them sent over to each regulatory body. Their job is to know what goes into a submission, what forms to use, and how it is supposed to get there. They work closely with medical writing and even help with the writing sometimes to get the job finished. A lot of companies lump the functions of submissions into strat, but some companies still keep them separate.

Labeling: They are in charge of saying what can go on the package insert, box, and other labeled texts, negotiating with the regulatory bodies to do so. You might not think that the difference between "used for the prevention of herpes" and "used for treatment: prevention of herpes" would have that much of a difference, but it absolutely does with the latter being preferred in some places even though it’s a little more convoluted. Labeling has to make sure every word has impact, meaning, clarity, and simplicity. They also have to decide the aesthetics of the package insert and label. Is it cluttered? Can the words from one part seep into another part and cause a confusing message? They figure all that out and create what you see as a consumer or provider.

Advertising and Promotion (Ad/Promo): You ever watch that commercial with the lady frolicking in a field of flowers and that one dude is biking with his kids and the narrator tells you it’s because they’re on that new antidepressant or, nowadays, that new psoriasis biologic? Of course you have because it’s everywhere. Ad/Promo is the team in charge of the TV commercials and magazine ads about certain drugs. Every person, demographic, and detail is specially chosen. The scariest part of the job is being very careful with what you say about the drug and how you display it to the audience. If even one word is misleading or incorrect, you will get the advertisement pulled, face severe fines, and can incur other massive penalties.

Policy: Policy is the team that tries to impact laws that impact the pharmaceutical world. They advocate to legislators on what policies need to change, including universal healthcare, to benefit both the companies and the patients. They work with organizations, like PQA and PhRMA, to promote the pharmaceutical industry.

Global Regulatory Affairs (GRA): Every major country has a regulatory body that handles whether or not a drug can get approved. Fortunately, for most countries/regulatory bodies besides Japan and a couple others, FDA approval is a huge boon to getting approval in other areas. GRA handles the submissions for the non-US regulatory bodies in every aspect, from strategy to submissions. They do get help from the other departments, but they are ultimately the subject matter expert for non-US bodies.

Commercial: Numbers, money, and making profit. They are the ones who are making the major decisions in terms of costs. Commercial handles mergers and acquisitions, and anything business-related, like partnerships with IDNs and hospital systems. If a patient cannot afford a drug, commercial and marketing develop the patient assistance program. Some companies have a separate patient-advocacy branch to help with this, though. It's important to note that not all pharmaceutical companies have the exact same structure and individual roles will change from company to company. Some companies even have overlap in their functional areas.

Marketing: Getting the drug marketed involves the advertising, promotion, and outreach of the product. You will utilize your commercial knowledge, economic strategies, and more to get the drug well known to the public in a positive light while also making sure what you’re saying isn’t unfounded or untrue to the available clinical information. Your primary targets here are healthcare professionals and patients because, ultimately, you want them to prescribe and utilize your drug.

Market Access: As the name implies, market access’ function is getting the drug accessible on the market. An example of this would be interacting with payors to get the drug on formulary. Knowledge of the payor system, formulary decision processes, economics, and managed care functions is helpful here. There is a lot of interaction (and confusion) between marketing and market access teams. If the drug won’t get approved on a formulary (market access), no doctor will prescribe it (marketing). Vice versa, if no doctor wants to prescribe it or no patient wants to use it, then no formulary will take it.

Business Development: No pharmaceutical company is able to stand alone and get a drug developed and marketed from start to finish without involving investors and external parties. Externally, BD handles licensing agreements, mergers and acquisitions (M&A), and partnerships with other companies. Internally, BD works with the executive team and other members to plan the future of the company.

Business Intelligence: BI works closely with BD to make sure that the company is ahead of the game. They monitor competitors, their therapies, and changes in the overall healthcare and commercial landscape. They do things, such as reviewing analytics, developing reports, and assessing key performance indicators, to guide the strategy of where the company goes.

Other: Under commercial, there is also sales, launch, and other roles. I know very little about this field outside of what I wrote, so if any of you commercial people want to pitch in, feel free to DM me.

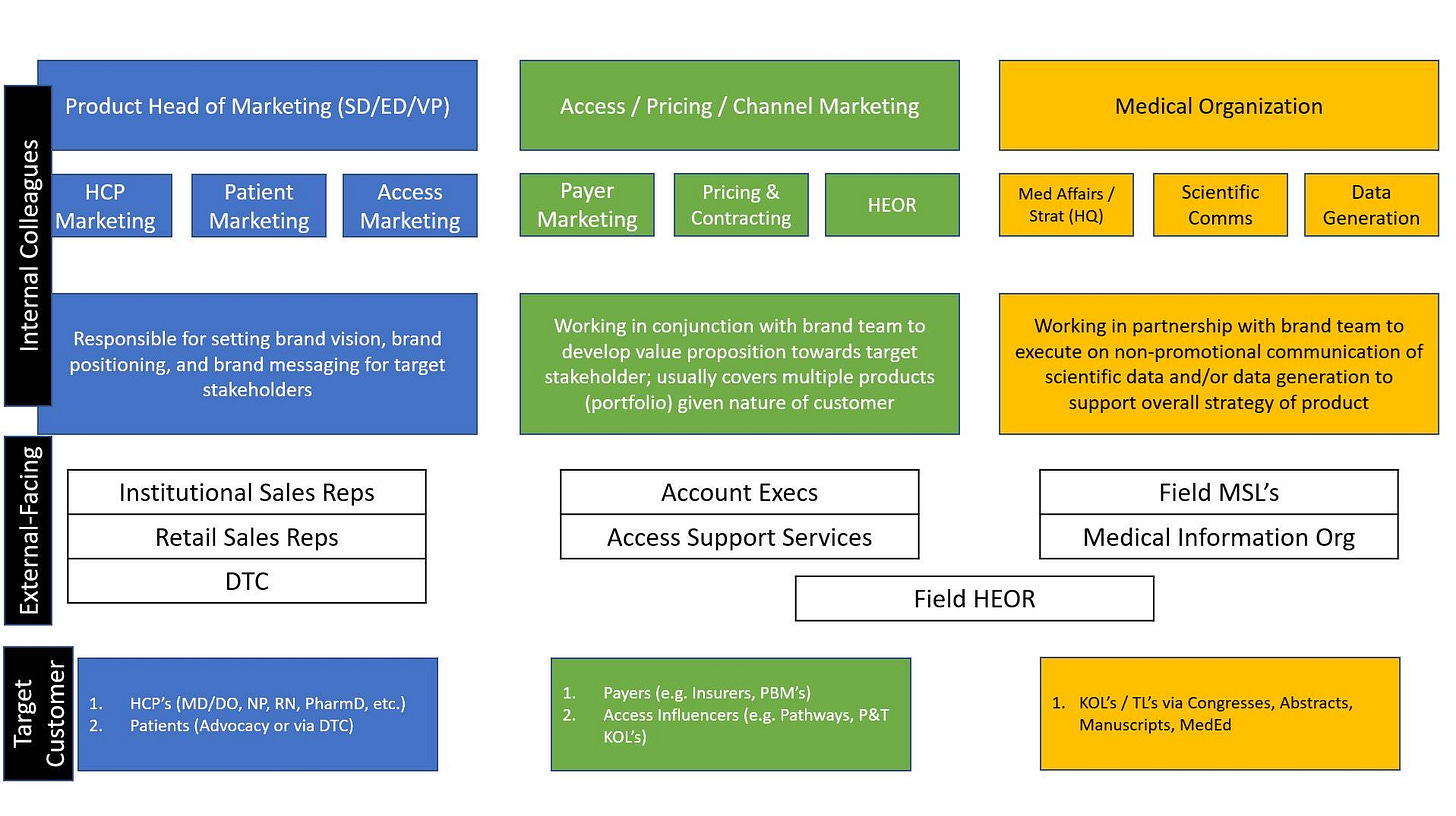

Huge shoutout to Pharmaz for explaining the marketing and market access sides of commercial as well as making this super helpful diagram highlighting the structure of a commercial team.

Clinical Development: This is where a lot of PharmDs and PhDs go. It's research heavy. Not in the wet-lab sense, but in the clinical research sense. You won't be pipetting and titrating. You'll be assessing patient populations, lab values, safety and efficacy of the drug, determining what your endpoints of the study will be, etc. This is where that fun in "how the drug works" comes in. Say you have a drug that works by inhibiting an enzyme which causes the disease. You have to pick a population that will respond to this therapy to make sure that it will work, so in your first trials, before you expand them, you want to pick patients who have high levels of this enzyme. This might mean you have to genetically test them and see if they have the gene that produces the enzyme, and if they do, make sure they have a phenotype that upregulates this enzyme production. Then if this one succeeds, you can start to generalize your patient populations a bit more in your phase 3 clinical trials. You have to be a scientist at heart: you have to pick apart data, clean data, and sell the best points while staying true to the science. When you first start off, you would be doing things like data cleaning (making sure that all data makes sense. If a patient is on a drug, they also need an indication. If they have a gap in time between therapies, there needs to be an explanation - you answer that) and trial rationalization (if anyone argues something about your trial, you have to defend it. If you can't, you make a trial amendment. The more amendments a trial has, the worse a trial looks, the less likely it gets approved).

Clinical Operations: Clin ops works closely with clin dev and regulatory to handle the less scientific, more technical aspects of clinical development. They locate sites, get the doctors to sign paperwork, figure out supply chain distribution and budgets, coordinate data cuts for submissions, make sure each site gets their drug, work with regulatory to get the sites approved, etc. Less science, more administrative.

Pharmacovigilance (PV)/Drug Safety: This can be seen as a branch under clinical development or under regulatory. Basically, you're monitoring adverse events and the patients who are receiving the drug. As adverse events are reported (most often by study investigators, prescribers, and patients themselves), you have to assess whether it's because of the drug or another reason (eg, concomitant medications, underlying medical history, ongoing global pandemic). The reported events are analyzed at both a single case and aggregate level, and summarized into periodic safety reports. This is one of the more clinically intensive fields and where lots of PharmDs go as well.

Case Processing/Management: This group receives and processes individual case safety reports (ICSRs), starting with data entry into structured (eg, numerical lab results, patient demographics) and unstructured (eg, qualitative lab results) fields. A narrative is then written, and a determination is made as to whether the company considers the event related or unrelated to the drug. An assessment is also made as to whether the event is considered expected or unexpected as per product labeling. Finally, if the event meets regulatory reporting criteria (generally serious, unexpected, related events), the case is submitted to regulatory authorities. This is a good entry-level position, but is increasingly becoming outsourced and/or automated.

Aggregate Reporting: This function may reside in PV, or under the umbrella of Medical Writing. Regulatory authorities require various periodic safety reports to be written at specific intervals (may be quarterly, semiannual, annual, or less often), depending on the report type and the life cycle of the drug. These reports summarize the overall safety of the drug over the preceding interval, with a highlight on any actions taken for safety reasons (eg, product recalls, study pauses or halts). This group authors these documents in collaboration with multiple functions including Clin Dev, Regulatory, Nonclinical, Stats, and others.

PV Science: A signal is a safety concern that we are unsure whether or not it is related to a specific drug (think J&J vaccine and those blood clots). This group is responsible for signal detection, which encompasses qualitative and quantitative methods for determining possible new risks associated with the drug. Qualitative methods include single case assessment (most common with well-documented clinical trial cases) and literature review, while quantitative methods include data mining the company’s internal safety database as well as regulatory and commercial databases to find events that occur disproportionately with the drug. Validated signals are evaluated to determine whether the event is considered related to the drug; if so, risk mitigation (eg, adding the event to the label, REMS program) may be warranted. This group may also support submissions, monitor trial safety, and respond to safety-related health authority queries.

PV Operations: No one knows, but there are PharmDs here too. Something something continuous process improvement and compliance.

Clinical Pharmacology: These teams are heavily involved in the early clinical development process. They model and graph the expectations of how the drug will work in the body among other functions. They look at all things pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics to gain a better assessment of the drug’s potential safety and efficacy. If the models don’t look good, then our new molecular entity gets shot down then and there. Basically, they’re the nerds who graph.

I just want to reiterate: Every pharmaceutical company has its own structure and roles will have minor to major differences. For example, some companies have medical writing under medical affairs because they work on publications and the sort more so than submission documents. Some companies don’t even have a designated medical affairs department. What I listed is only a generalization and will likely have minor to major differences depending on the company.

Getting into Industry

The hardest part of working in industry is getting into industry. Once you get that first entry-level job, your door opens up from a crack to a full-on corridor. Congrats! You’re now marketable! But how do you get there?

If you’re a student, get a fellowship. I cannot emphasize this enough. Many students steer away from the idea because you get paid less and have more responsibilities like teaching and whatnot, but the benefits greatly outweigh the “risks.” For one, most fellowships are rotational, allowing you to explore multiple different fields in a span of two years. A lot of people in pharmacy school switch to industry because they realized they didn’t like pharmacy. Well who’s to say you’re going to love medical affairs? A fellowship lets you explore your primary function as well as some of the other functions so you can really figure out what you like. Plus, it’s not like a fellowship silos you into that career for life; plenty of people switch after they complete their program, finishing a clin ops fellowship only to get hired into a clin dev role after. Another reason to take on a fellowship is you’re almost guaranteed to land a manager role once you finish, possibly even an associate director role (looking at you HEOR). I’m not going to harp on this too much because IPhO does a great job of that, but here’s the biggest reason (in my opinion) to apply for fellowships: if you don’t get a fellowship, you’re going to be applying for jobs when spring rolls around anyways, so why not get two shots at it? An entry-level job is hard enough to get and if it’s a contracting one, you’ll probably only be getting $30-35/hr anyways. That’s only ~$15k/annual pre-tax more than a fellow would make so that whole paycut argument becomes essentially null, especially after factoring in the speed of growth after a fellowship. So just go for the fellowship and give yourself a better two shots at getting into industry. Otherwise, you might be spending months jobless with your loans accruing and no job industry path set up in sight. It’s possible to get an industry job without a fellowship, but it’s just so much safer to go the fellowship route. The only reason to not go for a fellowship are if either A) Your CV is stacked and you know for certain you will get a job after or B) You already have a job lined up, offer letter and everything.

Someone from the server (shoutout to McK) wrote this great summary:

A. Guard rails of being a fellow, e.g expectations and understanding

B. Higher probability of professional development focus

C. Potential for more varied experience/exposure as a fellow

D. Overall trajectory. Likelihood of you landing anything higher than associate/sr associate is low, and most people I see take a year or two to move to manager then another year or two to SM

To get that fellowship, you’re going to want experience. You don’t absolutely need an industry internship (a good number of students get fellowships with absolutely 0 industry experience), but it definitely helps you figure out what you do and don’t like while also adding to your story come interview time. So how do you get that experience? I’ll try to keep this section brief because I can already feel IPhO drafting a cease and desist.

Research

This is the one of the best and absolute easiest things you can do that sets you apart from other candidates, yet so few students do it. Maybe that’s why it’s so good: because no one does it. A research project shows that you want to do more than just your didactic classes. It shows that you have an inquisitive mind and are willing to put in the effort to find those answers. Most importantly, it shows that you know how to conduct research which is the entire backbone of drug development.

Ideally, you want a research project that is in line with what industry wants while also showing translatable skills (HEOR, Patient-Reported Outcomes, literature reviews, claims data reviews, etc.), but if you have never done a research project, then really any pharmacy-related research project is good, even medication utilization reviews.

Try to stray away from wet lab projects. Again, any research is good, but wet lab research is more for PhDs and doesn’t hold the same weight as the other kinds of research projects.

Industry research > Clinical research > Wet lab research

Internships

Internships are obviously the best way to get direct industry experience, but they’re super hard to get. You’re one person in a pool of hundreds to thousands of candidates. It’s easiest to get one if you know someone in that company already, but if you don’t, just keep applying and you’ll (hopefully) get one eventually. If you don’t get it the first cycle, don’t feel discouraged. Just keep applying. I sent out 50-100+ applications each summer until I got one.

Some summer interns are fortunate enough to get internships at companies that can afford to keep them year-round as contractors. Keep this in mind during your internship and scope out of this is a possibility. A full year of experience >>>>> 3 month internship.

Leadership

Duh.

Don’t spend too much time and energy on this. It’s a few positive points on your fellowship application and can be a good talking point if you absolutely cannot get any other experiences, but the weight is relatively low compared to other things you can do and doesn’t provide direct experience. After graduation, you’ll probably never talk about these experiences again. A president position and one or two other minor roles is probably good enough. Don’t go crazy with 5 president positions, 3 VP positions, and bake sale coordinator because your time is better spent elsewhere.

If your school doesn’t have an AMCP or IPhO chapter, make one.

APPEs

APPEs are in a way easier to get than internships simply because there is less competition to get one. If your school already has industry APPEs, great, apply for them. If not, reach out to people you’ve met in industry companies and try to set one up. It’s a little bit of work, but it’s very much worth it and oftentimes the only direct industry experience students have.

FDA APPE is hella easy to get, looks good on CV, and is generally very low stress (almost a vacation). Only downside is that it can be expensive with travel and lodging for 5-6 weeks. That said, because so many people get FDA, if you have the chance to fill up on industry APPEs, prioritize them over FDA.

If you want an “off the menu” pharma APPE that you have to create yourself, it can take 12+ months to set up the contracts with your school. Invest in networking very early, ideally before P3 year.

Work experience

Whether it’s working in the clinical trials department of a hospital, reviewing medical literature for a medical content company, helping with prior auths for a managed care company, or something else, work experience is a fantastic way to get those alternative experiences under your belt. The hard part is finding them and being aware that they exist. LinkedIn is good for this.

Hospital intern positions are decent, but you can do better if you want to get into industry.

Retail intern positions are a dime a dozen. I pretty much skip right over these when reading applicants’ resumes.

Academic Competitions

So many of them exist. AMCP has P&T. IPhO has the VIP Case Competition. ACCP has clinical skills. Do them because they show your drive while also teaching you important aspects about industry and/or strengthening your clinical knowledge.

Network

This isn’t something tangible you can write on your resume. You’re not going to have a networking section on your CV where you namedrop everyone in industry you’ve ever breathed next to. The value of networking is that it opens up the doors to all of the above experiences. Maybe that one Pfizer lady you had a great conversation at that roundtable with has an internship opening in her department that she can refer you for. Maybe she can make one just for you. Maybe she can be the person you reach out to so you can set up an APPE there. Maybe she knows someone that can get you a fancy shmancy work experience that sets you apart from the other 9000 CVS interns. Everyone in industry will tell you to network, and for good reason, too.

So how do you network and where do you meet these people? Go to roundtables and have actual interesting conversations with them. Conferences are another way to meet people. AMCP has a conference buddy program specifically meant for this. Ask your existing network of who you should reach out to. Treat every conversation you have with someone in industry as if it were an interview, but don’t be too stiff or obvious about it. It’s a skill that comes easier to some people than others, but it’s a skill you should develop nonetheless.

GPA

Let me clarify something: GPA does not matter. So many students freak out about what their grades are and I cannot emphasize enough that almost no program actually cares. I know of exactly one fellowship that has ever asked about GPA and even then, I have no idea why they asked. Obviously do well in school and learn the material because that’s the whole reason you’re going 6 figures in debt, but don’t stress over that C in infectious disease unless you’re already barely floating at a 2.5. No job, fellowship, interview, or anything has ever asked for my transcript. Rho Chi has no power here.

When I was a student, I got paired with a conference buddy at AMCP Annual. She was a managed care residency program director who straight up told me “I couldn’t care less about your grades. At the end of the day, I know you graduated from a doctoral program. You have shown the ability to learn and that is what I care about. Beyond that, it’s about your extracurriculars, leadership, and personality. Grades mean nothing to me as long as you have ‘PharmD’ after your name.”

If you’re already a pharmacist, it’s a little bit/a lotta bit tougher. You’re going to want to apply to any and all entry-level positions you can. These positions include, but are not limited to:

PV Associate/Specialist

Clinical Research Scientist (CRS) - good if you have research experience

Medical Writer - both regulatory and medical affairs are good

Medical Information

Sales Rep positions

Clinical Research Associate (CRA) - can be useful, but not amazing

Quality Assurance - not amazing, only if you’re extremely desperate imo

Really, any position that has the title “Associate” or “Analyst” is a good start for you. Just be aware that you will more likely than not take a paycut, but the paycut will make up for itself in a few years time. A typical contract for entry level can range from the low, low, low side of $25/hr and be as high as $40/hr+. You’re mainly going to be looking at $30-40/hr because $25 might not be relevant enough to your field and $50 is likely out of your scope.

So where do you apply to and how do you get your name on the board? In terms of company types, you should definitely be applying to CROs like PRA Health Sciences, IQVIA, and Parexel. In terms of big vs small pharma, both are good in their own ways. Smaller companies may be willing to take a chance on people with little actual experience as they try to grow their own company. Bigger companies have the infrastructure and resources to support and train someone fresh in the field.

You should also be creating an account and uploading your resume and CV to websites like LinkedIn and Indeed. This is how recruiters will find you and it’ll make your job hunt a LOT easier. That isn’t to say you shouldn’t be submitting your own applications, though. Set up e-mail alerts at the career sites of all the companies you’re interested in. Some search terms you might consider are “PharmD”, “medical”, and “safety”, which will give you a lot of false positive hits, but should also return some relevant results. Apply as early as you can; you have a much better chance of HR/hiring manager seeing your resume if you apply within the first couple of days of the job being posted, compared to a posting that’s 30+ days old. Apply to as many positions as you can find - a lot of this is a luck/timing game. And obviously reach out to your network to see if anyone can refer you for a position. I hate myself for saying this cliche, but it’s more about who you know than what you know.

You can also consider applying to industry-adjacent positions. Industry supporting companies, like PhRMA, and patient advocacy organizations, like Cancer Care, have a lot of industry professionals in them. You’ll develop translatable skills and knowledge that you can then leverage into industry. You can also apply to the Investigational Drug Services department of a hospital where you’ll help manage clinical trials. The list of industry adjacents goes on and on. Your first step into industry doesn’t have to be at big pharma.

If you have spare time in your schedule, you can even see if it’s worth it for you to do a research project with a past professor to bolster your CV. Sure, you won’t get paid for it, but it’ll give you experience that might be valuable to industry. If you do this, don’t take the research approach a student would where any research is good research. Your time is a little less available as a working adult, so try to pick specific topics that industry would care about, like research surrounding health economics, real world evidence, outcomes, clinical trials, regulatory landscapes and projections, etc.

And the number one thing: do not get discouraged. Some people get their job in a few weeks. For others, it could take a few months. For the unfortunate crowd, it could take years. Just keep applying and figure out what you can do to make your application and interview better. If you aren’t getting any bites, it likely has to do with your resume, which leads us to our next section.

The Resume

Here is where a majority of people struggle. You’ll see people post all the time about how they’ve been applying to positions left and right for months and years with 0 hits. I can almost guarantee you it’s because of their resume. When you apply for these positions, you need to know how to sell yourself to industry. In this section, I’m going to give you tips followed by a few examples of what not to do and how you can fix them. This section will be the longest section because this is where people struggle the most. Disclaimer: I will be using real examples from real resumes I have received and reviewed. If you see your resume on here, sorry I put you on blast, but at least I gave you feedback at the time :) Please don’t hate me.

I also want to point out that a large majority of you should not spend money on a professional resume review. Those services typically only help out people in the business, finance, or whatever world that isn’t healthcare. They don’t have the healthcare knowledge on what terminology to use or how to tailor your resume to these kinds of jobs. They also cost a boatload of money (I’ve seen some going for $2k+ for additional career counseling). Reach out to your network to get free advice or help. They’ll know the field better and won’t cost you a cent.

Structuring: There is no one way to do a resume or CV. What I might find is the best way, someone else may find hideous. The general consensus, though, is that the first two pages need to have the most important things because most headhunters will only skim those first two. Because of the recommended reverse chronological order format, it can make it hard to get those most important roles up top, so it’s recommended to have a separate “Relevant Industry Experience” section if you have enough experience to warrant making a whole section for it (2+ roles). In my opinion, the most important things to highlight and should be at the top of your resume are:

Industry or industry-adjacent experience

Special projects

Research experience = Publications = Presentations

Other work experience

Leadership

2 and 3 can be switched. 4 is any other experience you have like staffing or anything else, but make sure you make those descriptions relevant to industry or have some kind of translatable skill (ex. Project management, team leading). If you cannot, don’t include it. Presentations could be in section 3 or even after 4 depending how relevant or irrelevant they are.

Unless your volunteering is with an advocacy organization or an organization that directly interfaces with industry, don’t include it. Remove any professional organization affiliations unless you have an active role in it like a leadership position.

General Tips:

Remember: you are a pharmacist. Your strength is in your clinical knowledge. Emphasize that. When you write descriptions, really flex this and show it because, assuming you have no other industry or research experience, this is a majority of the value you bring. People already assume all you do is count pills and stare at a computer screen. Prove them otherwise.

You are the most accessible healthcare provider. You know the patient journey, the struggle, and what they have to go through on a daily basis just to get their medications (prior auths, anyone?). Depending on the position, this could be pretty valuable information to have.

If you went to a half decent school, you did a journal club. That means you know how to sift through clinical literature, pick apart the key pieces, highlight the most important aspects, and criticize the flaws in the study. YOU HAVE PSEUDO CLINICAL TRIAL EXPERIENCE OR AT LEAST GENERAL, TRANSLATABLE KNOWLEDGE BASED OFF THAT. USE IT.

The person reading your application will more likely than not know nothing about pharmacy school. Keep the language relevant and understandable to the average person. This also means removing any pharmacy-only details. No one outside of pharmacy knows what an APPE is and no one outside of healthcare knows what an OSCE is. Remove this kind of stuff and change the language so that anyone and everyone can understand it. How you do that is up to you.

Just because pharmacy is saturated doesn’t mean your resume and CV have to be, too. Keep it to only the important details. If your CV is 4 pages of genuinely useful and good content, fine. But if it’s 8 pages including every IPPE you’ve ever done, absolutely trim it down. They’ll probably only read the first page or two anyways. For resumes, 1 page if you can, 2 pages max.

Side note: Remove your IPPEs. They are most likely not relevant.

Side note 2: Include only your important APPEs if at all. Nobody wants to see all 7 blocks of you doing med recs. Nobody will even read all of that. Keep it to the important parts or your resume will quickly find its way to the bottom of the recycle bin.

Side note 3: If your APPE is old (4+ years, maybe even less depending on who you ask), probably get rid of it. A 5 week experience you had almost a decade ago typically isn’t relevant anymore. Most people in industry get rid of it as soon as they graduate, but if you’re in retail and it’s the only industry experience you have, I can see why you’d want to keep it.

Try to incorporate the job description into your resume. This will help you get through the HR filters. For example, if under the requirements they say “must be able to detect adverse drug events,” you better change that “side effect” wording to ADE. Technically, they’re different, but for our situation, they’re the same. And don’t be afraid to use buzzwords. I’m not talking “synergy” or “team player” or whatever. I mean things that are actually important to the role. Throw in words like “ANDA” or “IRB Submission” if you have experience with them because they’ll help you get through both the computer filter and the reading filter.

If you have a “Skills” section, you more than likely should remove it. This section just takes up room without actually giving the reader any insight into who you are. Anyone can say they have “5 years of pharmacovigilance experience” when in reality they have none. Show your skills through your descriptions and functions. Make it so your descriptions include those keywords and exemplify how you actually have that 5 years of PV experience.

When making descriptions, people tend to write very vague and generic sentences that tell me nothing about what they actually did. You should almost always include three main things when writing describing a role: what did you do, how did you do it, and what was the goal of said task/function? That isn’t going to be applicable to every single function out there, but it’s a good rule of thumb.

Most importantly, make the resume relevant to industry in terms of both descriptions and roles. Too many times do I see resumes with things like “answered phone calls” or “scheduled technicians.” Industry doesn’t care about this. Only include things either relevant to industry, things that are fundamental to your job, or things that make you stand out over your general pharmacist or student. We’ll go over examples and you’ll see what I mean.

Example 1: Irrelevant information → Relevant information

Feedback: To be blunt, nobody cares about how many vaccines you gave or how many scripts you filled per day. If you’re applying for another retail position, sure, go crazy. But in industry, that means absolutely nothing. Make descriptions that they actually care about. If you were in a COVID-19 support role, that means you probably worked with VAERS. That’s a pharmacovigilance function right there. Highlight that. You could say something like “Performed adverse events reporting functions for COVID-19 vaccines through the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS).”

Example 2: Certifications

Feedback: For most positions, nobody cares about your pharmacy license. I have only ever heard of one (1) med info role that asked for it. No other position ever has. Remove any and all licensures and certifications that are not relevant to the role. If you are getting industry-relevant certifications, like a drug development course, sure you can throw it in. Otherwise, remove them. In the above example, if this person were applying to a med info position for Xarelto, I’d keep the AC management certification and that’s it.

Example 3: Descriptions

Feedback: For a med info role, this is really good! As a med info specialist, you are going to have to break down scientific and clinical data and present them to someone who may not know as much about the topic as you do. Tutoring does a great job of this. The problem with this one, though, is the description. It sounds very elementary and does not do the applicant much justice. Sure, the role might be simple, but the point of a resume is to sell yourself, and this one isn’t selling anything. Use more powerful words and descriptions. An example sentence would be “Creating educational content surrounding complex topics by breaking them down into easily digestible formats for various audiences.” Now the role lends itself to both med info AND medical education.

Also, please thoroughly proofread your application. I’ve seen so many CVs and resumes where small errors detract from the main point. It basically shows the reader you lack attention to detail and that you may provide sloppy work. In the above example, the first three letters of tutor are italicized while the rest are not. I don’t know how that happened, but it’s an easy fix that can hurt the applicant’s successes if the reader is anal.

Example 4: Descriptions

Feedback: Research is one of the best ways to set yourself apart for industry applications. This example could be such a good and important role, especially for a psych company like Alkermes, but it tells me absolutely nothing. What was the research project on? What was the methodology and what did you actually do? What were the findings? There’s so much potentially relevant information but so little detail that they might as well not include this on their resume. Add details and make them count towards industry.

Example 5: Keeping only what is important

Feedback: The first two presentations are so niche yet also broad that it just doesn’t have importance. They might be good if you’re applying to a poison control center, but not here. Get rid of them. On the other hand, presentation number 3 is actually very good. It was an entire hour (way more impressive than the 10 minute presentation) and is relevant to med info. Keep that on there, but also talk about it earlier on because it’s so relevant. This person had all their APPEs on their CV (note: don’t do that), but didn’t include this presentation as a description for any of them when it’s actually super relevant. Make a separate, more in-depth description for it on whatever APPE you did so it stands out. Don’t just copy and paste this same description and move it up, though. Talk about what the presentation was for, who the audience was, and what you talked about. Was it to the P&T Committee to discuss safety, efficacy, and value so you can help determine the drug’s place in the formulary? These are important details.

Example 6: Putting it all together

Feedback: So there’s a lot going on with this one, most of which I already said but I will repeat just to really drive it home.

APPE:

No one outside pharmacy knows what an APPE is - delete it and change the titles to something more universal.

Research Rotation:

Primary Investigator: “Myself” just looks lazy and unprofessional. Put in your name. If you want to highlight that it was you, I’ve seen people bold it to emphasize it was them.

This could be such a good experience again, but I know nothing about what you did. Remember rule #8 from above.

Albertson’s:

Don’t include how many weeks you did it. They have a general idea from your timeline and the difference between 3 weeks and 4 weeks in a community setting is minimal. Honestly, just get rid of it because it’s so irrelevant to industry and takes up space.

Health Clinic: Now this is where some good stuff can come in, but we need to highlight that good stuff.

You educated patients. Turn this description into something we discussed before regarding the breaking down of complex clinical information into something understandable by a less health-literate population.

No one knows what a journal club is. Change the wording to something like:

Analyzed and dissected ETHOS trial regarding COPD medications to determine strength of study and validity of findings.

Served as subject matter expert on essential tremors and delivered case presentation on disease state to audience of health care providers.

The first bullet is marketable to clin dev, the second bullet is marketable to medical affairs. Of course, these descriptions might not be wholly accurate on what you actually did, but it’s to give you an idea of what you should be going towards.

Although the journal club might have been less of what you did overall on the rotation, it’s what is most important to industry, so it should be moved up. I would reorganize the bullets under this section to 4, 2, 3, 1

Closing Remarks

Getting into industry is hard. Hopefully this made your path to get there a little bit easier. If you have any further questions, feel free to reach out to u/AdenosineDiphosphate on Reddit or email me at totallyarealemailipromise@gmail.com and I can try to answer any questions you may have.

If you’re in industry and disagree with something I said or want me to add anything I missed, message me and I’ll update my guide. I won’t take offense or anything. I’m here to make the best resource I can for people to get into industry, so any and all feedback is appreciated.

A huge shoutout to u/fleakered for helping me edit this guide and for adding a lot of details (pretty much all of them tbh) to the PV section because I know nothing about it and to Pharmaz for doing the same for marketing and market access.

Other resources:

Fellowship, industry, and other useful pieces:

Industry terminology:

Industry news:

Podcasts:

Syneos Health

Scrip Pharma-Intelligence

PharmExec

Lack the job description of the manufacturing organisation and the contract manufacturing organisation : within of manufacture, there are several departments: production, quality control (physical-chemical, biological), quality assurance (release, complaints, deviation, supplier, training...), validation, calibration, stability, master data, supply chain, planning....

There are a lot of jobs in the manufacturing organisation, not only in marketing authorization holder.

sorry for being a bit more ignorant because of the topic mentioned in the above post I don't even speak English natively so I'm a bit lost when I see long texts but that's not the point what I mean is that I am taking a certificate in BioWork and after finishing this course I feel a bit lost of what to do next any recommendations